An Interrupted life --an Unfinished Story

Over thirty years ago I started to write about my mother’s life. She was born in 1923 and died in 1968. She was no kind of public figure or important person to anyone but her friends and family, but she lived in an interesting time and wrote about it. I have her letters, journals, and college papers. Somehow, I haven’t seemed to get farther than a collection of bits and pieces—two introductions, some typed journals, some research into her academic life, a few vignettes. For many years this has been, for me, an unfinished project.

My house as a child was filled with my mother’s unfinished projects. Cloth was pinned to paper patterns, ready to be sewn. Knitted items were abandoned with needles stuck through the yarn. There was also, of course, her writing. Books started, ideas sketched but nothing finished, poetry, partially edited, in draft form. Even her education was unfinished—Her master’s degree from Brown in the 40s dropped at the very end by a change of heart and in the 60s at the University of the Pacific interrupted by her death. Her death at 45, of course, interrupted everything -- leaving everything unfinished. Her children grew up without her. Her poems were published for family—finished or not. Her letters and journals were collected and read by her daughter who felt something surely must be done with them despite her objections. In one poem Margaret wrote, in 1968, the year of her death:

Distorted images of self on

other people's shelves in other

people's neat closets

“It’s strange to think that I may no longer care.”

She wrote, “I want to write it all down, but no one should be allowed to read it until it is sorted out and understood by me. I’m not, I think, ashamed of my thoughts but only of their unfinished nature—I don’t want anyone else to finish them. I want to do it myself, but I have to write them down first. Marriage and motherhood are the most inhibiting of all.”

Margaret Vogt Fairbrook

February 15, 1968

Against her will and wishes I feel impelled to finish these thoughts -- to write her story, to sort out the tangle and to make it make sense. In a sense it is a story that belongs to me, to my sister, to my daughter, to my granddaughters, as much as it belongs to her, to my mother. Or, if that is self-serving thinking, to use her words from her notes from her (never-finished) poem, “Distorted images of self on other peoples’ shelves in other People’s neat closets” The images of her that I write will, of course, be distorted, but that doesn’t mean that they won’t be true all the same.

My closets are not neat, but her thoughts and images of self are filed away neatly in a filing cabinet, waiting for me to do something with them, to try to finish, in some way, this unfinished project. My sister, who was my best writing audience and most enthusiastic cheerleader is no longer here. I did not come close to finishing it for her to read, and as I write, I mourn her absence and miss her deep understanding of what I write. I have found out recently that my daughter is going to have a daughter. If I think of her as the audience, perhaps that will help.

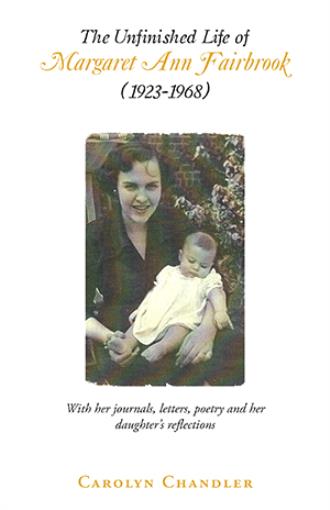

I look at a picture of myself thirty-five years ago, smiling at my daughter who is squirting bubbles from her squirt bottle and laughing delightedly. I have pictures of my mother smiling at me in the same way. I remember her smiling at babies—she loved babies. She didn’t love very many things, but she loved babies as much as she loved poetry. She loved her friends with a fierce loyalty—I don’t know how I knew this, but I felt it. Perhaps children feel their parents’ emotions without knowing exactly what they are noticing or feeling. Of course, we knew that she loved us, her children, although the word love wasn’t used much in our family.

Everyone who knew her remembers my mother sitting in an overstuffed living room chair, reading writing, smoking: the table next to her littered with lipstick-stained coffee cups, cigarette butts and crumpled pieces of rejected butts. Tendrils of smoke curl up from a littered ashtray. When I came how from school, she lifted her head from her book to smile as I came in. She would lay down her book and ask, “How was school?” This was my invitation to sit on the couch and talk to her. I don’t remember what we talked about, but it was comfortable and intimate. I have other memories of her, and I am sure others do as well, but whenever we talk about her, it’s the woman in the chair we talk about.

My house as a child was filled with my mother’s unfinished projects. Cloth was pinned to paper patterns, ready to be sewn. Knitted items were abandoned with needles stuck through the yarn. There was also, of course, her writing. Books started, ideas sketched but nothing finished, poetry, partially edited, in draft form. Even her education was unfinished—her master’s degree from Brown in the 40s dropped at the very end by a change of heart and in the 60s at the University of the Pacific interrupted by her death. Her death at 45 interrupted everything — leaving everything unfinished. Her children grew up without her. Her poems were published for family—finished or not. Her letters and journals were collected and read by her daughter who felt something surely must be done with them despite her objections. In one poem Margaret wrote, in 1968, the year of her death:

Distorted images of self on

other people's shelves in other

people's neat closets

“It’s strange to think that I may no longer care.”