On the Border

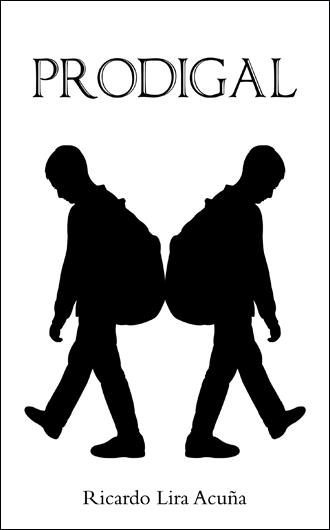

I was born on a border. Or at least that’s what it looked like on a map. Nopales, Arizona was a dot by a thick line dividing the United States and Mexico, and it had a dot reflection in Nopales, Sonora, Mexico. Except for my teachers, everyone I knew on both sides of the border was Mexican, and the two Nopaleses might as well have been one. I too felt a thick line running through me, splitting me in two, between the American side and the Mexican side. The year was 1985, and I was a sophomore. Sophomore, I later learned, meant “wise fool” in Greek.

Nopales High School, Algebra II, fifth period, chapter test. It was a zoo in there, a cacophony of English and Spanish. A wad of paper pelted the back of my head. Even if I knew who threw it, I wouldn’t be able to prove it. And if I acknowledged it in any way, I’d be pelted again. So I ignored it. I was used to it.

A wad of paper landed on Mr. Ibsen’s desk. He stood up. A tall, lanky man in his 60s with graying hair and a full beard, he looked rather drab and frumpy in his long-sleeved flannel shirt, knit tie, corduroy pants and hiking shoes, but the man had an intense intelligence that shined through his blue eyes. “You don’t have until the return of Halley’s Comet, so finish your exams and turn them in!” he raised his voice at them, his pale face flush.

They quieted down, not because he warned them, but because he interrupted them. They didn’t care. Not about the test. Not about the class. Not about him. Not about anything really. Well, they did care about one thing. So they laughed him off and continued socializing.

“You should all follow Ray Mundo’s example. He finished early and even got the extra credit,” said Mr. Ibsen.

They booed me and called out, “¡Pinche nerdo!” I was used to it.

Mr. Ibsen got up from his desk and handed my test back–’110/100’ scribbled in red ink at the top. “Ever think about going to a private school?” he asked.

“My sights are set on Harvard,” I said, pressing back my thick glasses with my skinny index finger.

Mr. Ibsen turned to me and furrowed his bushy brows, “I mean a private high school. Where you’ll be surrounded by equals. And it’ll vastly improve your chances of getting into Harvard.”

“I wish. But I live in a trailer.”

“What if I have a friend who can help? Are you interested?”

The chaos got so great he had to yell at them, “That does it! Pass up your exams, you bunch of cretins!”

He took a piece of paper, wrote on it and set it down on my desk.

I read it as I made my way across a concrete walkway connecting the red brick buildings sprouting in the middle of the sun-baked desert. The place was crawling with loud teenagers whom I avoided, but in order to get to my bus, I had to pass through the center of campus where the jocks, the cheerleaders, and worst of all, los popis held court with their good looks, trendy clothes, and annoying socializing.

“Like gag me with a spoon!” exclaimed one of los popis dressed like a valley girl wannabe.

I turned to find her grimacing at me. I’d seen her before. She was a senior, and every guy in school lusted after her, even me, I was ashamed to admit.

“A plaid shirt? Green corduroys? Purple socks? Like grody to the max!” she said aloud for everyone to hear.

Her letterman-jacket boyfriend, with whom she was holding hands, snatched away from me Mr. Isben’s piece of paper.

“Hey!” I complained.

“Mr. Millstein? Is this your boyfriend and his phone number?”

“It’s my golden ticket,” I said. “You know, like Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.”

He stared me down over his Ray Ban sunglasses. I was expecting my face to meet his fist at any moment.

“Fucking Waldo,” he said. “You know, like from Van Halen’s Hot for Teacher video.”

“Just give it back,” I dared on.

“Or what?!” he barked in my face. He dangled the paper above my head as I jumped up for it and missed. He stuffed it in his mouth and ate it.

I turned away, much to the jeering and whistling of los popis. Sure, many a time I wished to dress like them, be popular like them, and be rich like them. Truth was I hated them. I wanted to be better than them. I knew I was smarter, but I didn’t have anything to show for it other than good grades. And they didn’t care about grades.

“Is everything copasetic?” asked my best friend Samuel who caught up to me. While I had dark brown skin, Samuel looked white, his name sounded white, and he had a white stepfather. But Samuel was actually born in Mexico. I was of medium height, and he was tall. I was thin; he was thinner. I wore thrift-store clothes and K-mart black dress shoes; he wore a Members Only jacket, Levi’s jeans and all-white Nike high tops. My hair was perfectly parted to the side and licked back with hair tonic; Samuel’s was short, straight and natural-looking. I looked like a 1950’s poster boy, while he actually looked like he fit in with the times.

“You ever think about stepping into a time-space portal and getting the hell out of Nopales?” I asked him.

“Like every nanosecond.” he said. “Dare I ask what was on that paper?”

“An escape.”

“So what’s plan B?”

“No plan B, thanks to photographic memory.”

I had to run to catch the yellow school bus that was pulling out of the parking lot.

“Maybe you can come over for Star Trek and Pac-Man this weekend?” Samuel called out as the door just closed behind me.

His mom was waiting for him in their station wagon. He lived in a nice house on a hill, and he had his own room with a TV, stereo, model planes, and an Atari home computer.

I sat at the front of the bus, like I sat at the front of the classroom. My mind raced as I looked out the window. For once, I wasn’t jealous of the students who drove to school. Not even the mongrels shouting and shooting spit wads in the back annoyed me that afternoon. All I could think about was prep school. But which one was Mr. Ibsen talking about? There was no such animal in Nopales. Perhaps in Tucson, which was an hour north? I would much rather go to school in Tucson with a population of approximately 400,000 than Nopales, which was a ranch by comparison with approximately 19,000.

I closed my eyes and pictured myself in a tie, even though I didn’t own one, and a coat with the school’s crest on the heart pocket, and I sat at the head of a group of like-dressed students debating academics, and I spoke with a British accent like The Beatles, and-

A spit wad hit the side of my face. I wiped it off. “Last stop!” called out the bus driver. I gathered my backpack and sweater and scrambled out with the few remaining kids. They scattered toward their houses while I stood by as the bus kicked up some dirt and sped off.