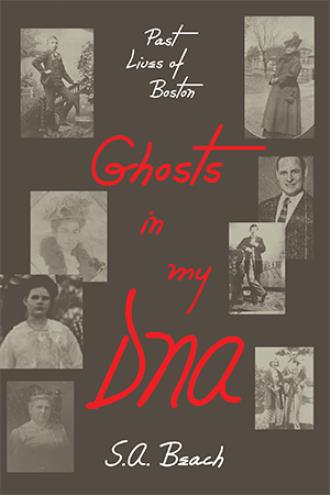

Ghosts in my DNA

Past Lives of Boston

by

Book Details

About the Book

A young science teacher left her New England home and family behind to build a new life among people of the Caribbean on the sun-drenched island of St. Croix. She built an extensive professional life and with her Crucian husband raised a beautiful biracial family who call the island home. But as the decades turn, a haunting question begins to surface: Why did she really leave all her family and everything that was familiar behind? Was her momentous move a choice, or was she driven by forces beyond her own consciousness?

The search takes her on a circuitous hunt through old library records, museums, and ancient cemeteries throughout Massachusetts. The research revealed a paternal lineage stretching back to the Winthrop Fleet of 1630. She vicariously relives their experiences in each generation beginning with interactions with the Wampanoags. The early colonial life included public whippings, consequences of the Pequot War, and a Revolutionary War patriot. A Prussian immigrant enters the lineage and raises a family in the midst of the Boston abolitionists in 1850’s. A son joins the cause of the Civil War at sixteen. A Vaudeville actor becomes a household name in 1880, and early theories in science are developed by an erudite uncle with eccentric beliefs. She finds commonalities linking the generations of her father’s family to her decision to break away from all that was safe and familiar. You may find hints of your early New England colonial ancestors among the many profiled and mentioned in these pages.

Website: sabeachauthorusvi.com

Email: sabeachauthorusvi@gmail.com

About the Author

S.A. Beach is a graduate of Boston University and a New England native relocated to the Caribbean since 1980. She retired after 35 years from the Virgin Islands Department of Education. Mrs. Beach recently started writing about the family heritage left behind in Massachusetts.