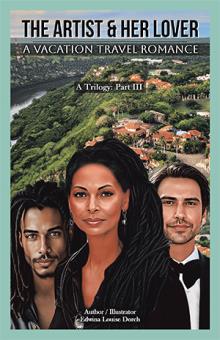

The Artist & Her Lover

A Vacation Travel Romance (A Trilogy: Part I)

by

Book Details

About the Book

This fast-paced travel romance is Part I of a trilogy series of books. It's an upmarket romance involving a Caribbean love triangle.

Autumn Simmons, an American naïve artist living on a Florida barrier island, travels to Jamaica, and there she lives in the Kanopy (Tree) House in the Blue Lagoon.

While there, she meets two men who vie for her affection.

One is Colin Acieta, born and raised in Italy, who embodies old-world Western art traditions … Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Raphael.

The other, DeAngelo DeCosta, a Rastafarian Djembe drummer, who lives surrounded by artists painting large, bright, open-air murals on buildings to uplift Kingston’s garrison’s poor.

Will Autumn choose to remain in Jamaica, with the Rastafarian, DeAngelo, and embrace free, open-air, community mural art?

Or,

Will Autumm choose Acieta, and live surrounded by the Vatican,

the Sistine Chapel, the Colosseum, Roman statues, and

masterworks of art?

The Author encourages readers to view the artwork of naïve artists, Tyrone Johnson and Synthia Saint James, and the Florida Highwaymen, and to listen to instrumentals by Chris Botti, like Emmanuel, Nessun Dorma, and Cinema Paradiso.

Author / Illustrator, Edwina Louise Dorch, won the American Writing Award for best inspirational novel in 2023 and was a finalist in the crime genre in 2024. She is a psychologist who teaches art therapy on a barrier island off the Coast of Florida. And, her paintings are shown in galleries along the Florida A1A highway.

About the Author

Author / Illustrator, Edwina Louise Dorch, won the American Writing Award for best inspirational novel in 2023 and was a finalist in the crime genre in 2024. She is a psychologist who teaches art therapy on a barrier island off the Coast of Florida. And, her paintings are shown in galleries along the Florida A1A highway.